Why caste census is important for SC.STs?

- Why India is still stuck with caste surveys and quota?

Why India is still stuck with caste surveys and quota?

Caste was always a reality of life in India and in many places, it still is

)

India has been gripped by a new census. No, not the national one that is yet to be conducted, this is a caste census from the state of Bihar.

It’s exactly what it sounds like - the population data was collected based on 17 indicators and one of them was caste. The headline result is this: two groups make up 63% of the state’s population - the OBCs (or the other backward classes) and EBCs (the extremely backward classes).

Now, you don’t do a census for the love of numbers, you do it to make policy. So, what’s the policy goal here? More reservation and more welfare schemes. It’s become a political lightning rod. The opposition parties want a nationwide caste census, the ruling party says - not interested.

Keeping the politics out for now, let’s look at the caste census and reservation. Why is it so important? When was it last done? And has it delivered in the past?

First things first. What is caste?

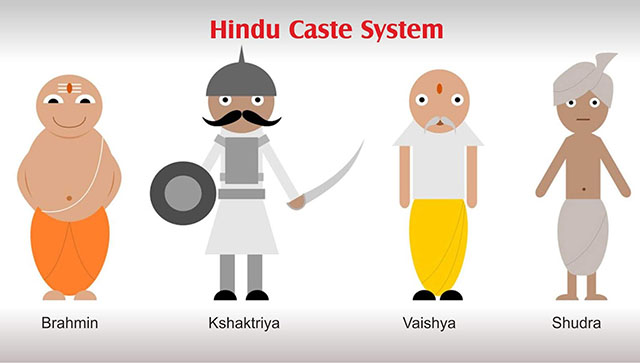

Simply put – it’s a system of social hierarchy. People are ranked based on their birth. Hindu texts talk about four major caste groups. At the very top come brahmins, your priests and teachers; then comes kshatriyas, the warriors; vaishyas, the traders; and finally, shudras, the menial workers.

Beyond these four, there is another group - the Dalits, or the untouchables.

This group was considered outside the caste system. They were cleaners and cremators.

Caste was always a reality of life in India and in many places, it still is. But when the British came, they formalised it. Their reason was simple – you can’t govern what you don’t know, so divisions based on caste were easy to understand, or so they thought.

A British idea

The British wanted to neatly divide India’s Hindus into four categories. They were in for a surprise. In Benares, in 1834, there were 107 castes of brahmins, so the four-category system wasn’t always the norm. The British made it so and they knew it. Here’s what a British official who organised the Madras census wrote: “whether there was ever a period in which the Hindus were composed of four classes is exceedingly doubtful".

Despite that, they pushed on. From the 1880s, the official census began. Caste data was also collected back then. This practice would continue until 1941 - the last census where caste data was collected. But in 1941, this data wasn’t published. The British called it an enormous and costly table, so they said no more caste data, which means, our last caste estimate is from 1931. That’s around 93 years ago.

When reservation made sense?

Did reservation exist during this time? In some places, yes. The princely state of Mysore was among the first to do it. In 1921, they reserved seats for backward communities. Basically, a quota in government jobs and education. Soon, Madras and Bombay followed. It made perfect sense back then.

Here’s some data from the Madras presidency - Brahmins made up 3 per cent of the population there but they held 80% of all official posts. So back then, reservation was necessary. In the 1930s, it was extended to government - not without some drama though.

A flashpoint and compromise

In 1932, the British had proposed separate electorates for backward communities. Now, this is different from reserved seats. In reserved seats, everyone votes. The only condition is that candidates must belong to backward communities - say Scheduled Caste or Scheduled Tribe.

Separate electorates is different. Here, both candidates and voters will be from backward communities.

This decision pitted two stalwarts against each other - Mahatma Gandhi was against it,

DR.BR Ambedkar supported it.

To convince Dr.Ambedkar, Gandhi began a fast unto death. Eventually, Ambedkar relented. He agreed to reserved seats instead of separate electorates. This would continue even after Independence. India’s constitution permitted quotas and reservations. Not for everyone though, only two marginalised groups - the SCs - or the scheduled castes - and the STs - or the scheduled tribes.

One-two of reservation

This reservation can be divided into two types -

(1) one is the political one, which is temporary;

(2)the other is the social kind - our jobs and college seats.

The political reservation meant quotas in elected bodies like Parliament and state assemblies. That was supposed to be re-evaluated after 10 years. But nowadays, there is no evaluation, there is only extension. The latest was in 2019 - the SC-ST quota was extended by another 10 years.

The second type of quota doesn’t have a time frame. Many people say the founding fathers wanted it to be temporary, but the Constitution doesn’t mention it. Either way, this was the set-up after Independence, and it remained so until 1979. That’s when a new commission was set up - the Second Backward Classes Commission. You may know it as the Mandal commission.

It was headed by BP Mandal, a former chief minister of Bihar. He took around two years to finish the report. In December 1980, it was submitted and the big headline was this - OBC communities should get 27 per cent reservation, both in jobs and in colleges. It wasn’t implemented though! Because by 1980, the government had changed.

A political and legal landmine

Nobody touched this report again for 10 years, but in August 1990, then prime minister VP Singh dusted out the Mandal report. In fact, he went a step further. He decided to implement it. There were massive protests across India. Hundreds of students hit the streets in major cities, dozens of them set themselves on fire but the government pushed on. The 27 per cent quota was implemented for OBCs. So India’s reservation pie looked like this - 15 per cent for Scheduled Castes, 7.5 per cent for Scheduled Tribes and 27 per cent for OBCs. The total came to 49.5 per cent.

Just one problem though. The Mandal report triggered a new era of politics. Leaders hijacked the narrative. Instead of social justice, reservation became a political tool. If you want community X to support you, give them quotas. That became the trend.

So, to prevent that, the Supreme Court intervened. In 1992, they delivered a historic verdict - that quotas cannot be more than 50 per cent. Things have changed though. A new verdict says the 50 per cent limit is flexible.

But we’ll get to that later.

It’s been three decades since OBC reservation was introduced, and around eight decades since the SC-ST one. The big question is - has it delivered? And if not, why are we not trying something else?

In 2021, the government submitted some data to the Supreme Court. They had surveyed 19 ministries, and this was their finding - SCs made up around 15 per cent of all employees, STs made up 6 per cent and OBCs around 17.5 per cent. We are talking about government workers here. Now compare this to the reserved quota. The SC numbers are on par but the other two are not.

While 27 per cent jobs are reserved for OBCs, they make up only 17.5 per cent. That’s a huge gap and within this gap there is a bigger problem. Most quota workers are low-level employees. In 2012, around 40 per cent of public cleaners were SCs. Even among OBCs, the biggest chunk is employed in such jobs. As you go up the hierarchy, they simply disappear.

Let’s look at the coveted all-India services - your IAS and IPS. In the last five years, around 4,300 appointments have been made. OBCs, SCs and STs made up 27 per cent of that, but their share of population is much higher - closer to 75 per cent. Same with colleges. Around 42 per cent of teaching posts reserved for these communities are lying vacant. 42 per cent! so reservation has not levelled the gap. It has made gains, yes, but it hasn’t solved the problem.

At the same time, a new one has emerged - everyone wants a quota nowadays. At first dominant communities had rejected the idea of reservation but clearly, it’s not going anywhere. So their new strategy is this: ask for their own quota. There are examples from across India - the Patel community in Gujarat wants quotas, the Marathas in Maharashtra, the Lingayats in Karnataka, the Jats in Haryana. These are politically powerful communities in their states, but now, they want quota.

So where does it end?

The Supreme Court had some interesting takes on reservation. This was last year, when they said the 50 per cent cap on quota is flexible. Here’s what one judge said: “at the end of 75 years of our Independence, we need to revisit the system of reservation in the larger interest of the society as a whole”. Here’s another judge: “reservation is not an end but a means — a means to secure social and economic justice… reservation should not be allowed to become a vested interest”.

Unfortunately, that’s what it has become - a vested interest, a political tool. That doesn’t mean reservation hasn’t helped. It has made very important contributions to social justice. But it hasn’t solved the root problem.

And where does the caste census figure in this conversation?

Well, numbers drive policy. That’s the idea behind the caste census. We already collect SC and ST data every 10 years. The demand is to collect OBC data as well. The previous government did so in 2011 but that information was never published. The current government says the data is unusable. Hence the demand for a new one.

There are two reasons why quotas still persist in India.

One is political - quotas help win elections and every political party has used them.

Two, because there is no alternative. Governments have failed to answer the most important question – if not quota, then what?

Do you have a plan to change mindsets? Because let’s face it, everyone is against the caste system. Unless of course, their children decide to marry outside their caste, then, it’s a big issue.

So, India is stuck with this imperfect system. It’s ironic really. Our goal is to create a casteless society, yet our policy is to define and reserve based on caste.

To Uplift the SC.STs on par with others..

1) India must distribute the public lands 25% to the landless SC.ST like America distributed share of lands to Black people when they gave rights to Blacks.

2) Reservation in promotion must be implemented for OBC also.

3)Political Reservation must be implemented for OBC also.

4)Special drive to be conducted to fill up the vacancies reserved for SC.ST.OBCs immediately.

5)Reservation must be implemented in Private Sector in EMPLOYEMENT like Reservation in Private Schools and colleges.

Sivaji.A

Please follow us in WHATSAPP CHANNEL.

Follow the Indian Untouchables.News channel on WhatsApp: https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029VaOwmSMEgGfKBvRSHX2T

Comments

Post a Comment