26.08.24.untouchables news Chennai.*India.by Sivaji.team.9444917060

Buddhas teachings...The Foolish Son

Once, in the city of Vaisali there lived a royal barber who was a devoted follower of the Buddha. One day, he took his son along when he went to the palace to work. There, his son got attracted to a very beautiful girl all dressed up like a goddess and wanted to marry her. His father told him to forget about the girl as she belonged to the royal family and would never agree to such a proposal. But the son refused to eat and drink until he got married to her. All his family members tried to reason with him, but failed. The young lover was so disappointed and heartbroken that he passed away. After performing his son’s last rites, the father went to meet the Buddha. The Buddha told him, Your son has died by setting his heart on something which he could never have. The barber could say nothing but weep for his son’s foolishness.

*JAIBHIM*

&

Good morning

Here is Dr Babasaheb's Speech during mass conversion on 14th October 1956*

1.Your behaviour should be such that other people will honour and respect you.

2.Do not think that this religion means we have got stuck with a corpse around our neck.

3.As far as the Buddhism is concerned, the land of India is of no account. We must resolve to follow Buddhist religion in the finest way.

4.It should not happen that the Mahar people brought the Buddhism to disgrace, so we must have firm determination. If we accomplish this, then we will thrive ourselves, our nation, and not only that but the whole world also.

Because the Buddhist religion only will be the saviour of the world. Unless there is justice, there will be no peace in the world. This new path is full of responsibilities*

https://baws.in/books/baws/EN/Volume_17_03/pdf/553

*Jaibhim Ravikeerthi*

💙💙💙💙💙

Read more at: https://www.deccanherald.com/india/telangana/equal-share-for-dalits-a-tale-of-triumph-after-three-decades-of-struggle-3163148

Understanding the creamy layer verdict Dalits are upset about

.jpg?w=480&auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max)

The agitation was held despite the government assuring that the creamy layer part of the verdict will not be implemented. SC/ST reservation is such a hot potato that no one with any sense of political survival would want to go anywhere near disturbing it. The ruling BJP burnt its fingers in the run up to the general elections this year, as its loose cannon in Karnataka, Anantkumar Hegde, tried to justify the party's 400-paar pitch, saying it needed that many to change the Constitution to purge it of the distortions introduced by the Congress. Though the BJP promptly disowned his statement, the Opposition cited it as evidence of the ruling party's ulterior motive of doing away with the quota system. The result: Dalits moved away from the BJP in UP and the party lost its simple majority in the Lok Sabha.

Days after the court's verdict on August 1, Union minister Chirag Paswan said his Lok Janshakti Party (Ram Vilas) will file an appeal against the ruling. He pointed out that the Dalit quota was not just on account of social backwardness but due to the historic injustice of untouchability faced by the community, adding the verdict had failed to factor it in.

Fact check

But a quick fact check showed that the 6:1 judgment was very much alive to the scourge of untouchability. In fact, there were over 56 iterations of the word untouchability across the verdict, including in the footnotes. For example, paragraph 101 of the majority verdict authored by Chief Justice of India D Y Chandrachud says, "The castes which are included within the Other Backward Class suffer from a certain degree of comparable backwardness but the form of social backwardness amongst them may vary. As opposed to this position, the Scheduled Castes suffer from a common form of social backwardness through untouchability."

Sub-division

Sub-classification came into play after a landmark nine-judge bench ruling in the Indra Sawhney case in 1992. It ruled that the sub-division of the OBCs was valid under law but not applicable to SC/STs. It also allowed the exclusion of the creamy layer within OBCs from the ambit of reservation.

However, various states, including Punjab (50% quota for Balmikis and Mazhbi Sikhs in direct recruitment) and Andhra Pradesh, passed laws for sub-categorisation of SCs. In 2005, a five-judge bench in the E V Chinnaiah ruling held that the SCs cannot be sub-divided as they form a homogenous class. Fifteen years later, another five-judge bench found the need to revisit the Chinnaiah verdict and sent it to a higher bench. Chief Justice of India D Y Chandrachud constituted the seven-judge bench and began hearing the matter from February last.

The bench examined the interplay of Articles 14 (equality before law),16 (reservation in jobs), 338 (National Commission for the SCs) and 341 (powers of President to specify castes, races or tribes that will be classified as SCs) and concluded that the SCs do not satisfy the definition of a homogenous class.

"Historical and empirical evidence demonstrates that the Scheduled Castes are a socially heterogeneous class. Thus, the State in exercise of the power under Articles 15(4) and 16(4) can further classify the Scheduled Castes if (a) there is a rational principle for differentiation; and (b) the rational principle has a nexus with the purpose of sub-classification," the majority ruling authored by Justice Chandrachud for himself and Justice Manoj Misra said.

Justices B R Gavai and Pankaj Mithal authored separate but concurring verdicts while justices Vikram Nath and S C Sharma in their separate rulings agreed with the positions of justices Chandrachud and Gavai. All of them said the Indra Sawhney verdict does not limit the application of sub-classification to the OBCs. Justice Bela Trivedi wrote the sole dissenting verdict.

Exclusion principle

While the CJI did not get into the creamy layer debate, the lone Dalit on the bench, Justice Gavai, dwelt at length on it and ruled that it should apply to SC/STs as well. He built his argument by citing a 1981 ruling of Justice V R Krishna Iyer in the Akhil Bharatiya Soshit Karamchari Sangh case, where the latter had observed that "A swallow does not make a summer. Maybe, the State may, when social conditions warrant, justifiably restrict Harijan benefits to the Harijans among the Harijans and forbid the higher Harijans from robbing the lowlier brethren."

Justice Iyer went on to suggest that the administration could innovate to weed out the creamy layer among the SC/STs, but it shall not be imposed by the court.

Justice Chinnappa Reddy in the K C Vasanth Kumar case ruling in 1985 said, "a few members of those caste or social groups (SC/STs) may have progressed far enough and forged ahead so as to compare favourably with the leading forward classes economically, socially and educationally. In such cases, perhaps an upper income ceiling would secure the benefit of reservation to such of these members of the class who really deserve it."

In the M Nagaraj verdict in 2006, the court applied the principle of quantifiable data and creamy layer even for SC/STs. But the Jarnail Singh case verdict in 2021, held M Nagaraj's requirement of quantifiable data of backwardness of SC/STs as invalid. But it upheld the applicability of the creamy layer principle even to SC/STs taken in M Nagaraj. In doing so, Jarnail Singh was basically relying on the judgment of a seven-judge bench in N M Thomas case in 1975 that considered the question of affirmative action for SC/STs.

In N M Thomas, Justice Krishna Iyer observed that the state is entitled to take steps to weed out the socially, economically and educationally advanced sections of the SC/STs from the applicability of reservation.

Unequal treatment among unequals

"By judicial interpretation, the equality enshrined in the trinity of Articles 14 to 16 of the Constitution has been considered to be equal treatment among equals and unequal treatment among unequals. The question that will have to be posed is, whether equal treatment to unequals in the category of Scheduled Castes would advance the constitutional objective of equality or would thwart it? Can a child of IAS/IPS or Civil Service Officers be equated with a child of a disadvantaged member belonging to Scheduled Castes, studying in a Gram Panchayat/Zilla Parishad school in a village?" Justice Gavai questioned.

Education and the other facilities that would be available to a child of a parent of the first category would be much higher, maybe the facilities for additional coaching would also be available; the atmosphere in the house far superior and conducive for educational upliftment. In comparison, the child of a parent of the second category would have the bare minimum in education and the facilities of coaching, etc., would be totally unavailable, the judge reasoned.

Disparities and social discrimination, which are highly prevalent in the rural areas, start diminishing when one travels to the urban and metropolitan areas, he observed. "I have no hesitation to hold that putting a child studying in St Paul's High School and St Stephen's College and a child studying in a small village in the backward and remote area of the country in the same bracket would obliviate the equality principle enshrined in the Constitution," Justice Gavai said.

He agreed that some SC/ST officers in high positions are doing their bit to pay back to society by providing coaching and other facilities to their less advantaged brethren. "However, putting the children of the parents from the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes who on account of benefit of reservation have reached a high position and ceased to be socially, economically and educationally backward, and the children of parents doing manual work in the villages in the same category would defeat the constitutional mandate," Justice Gavai argued.

But the parameters for exclusion from affirmative action of SC/STs may not be the same as that applicable to the OBCs. If a person through the SC/ST quota gets the position of a peon or a sweeper, he would continue to belong to a socially, economically and educationally backward class. But those who used reservation to reach the high echelons in life cannot be considered to be socially, economically and educationally backward so as to continue availing the benefit of affirmative action, he said.

"I am therefore of the view that the State must evolve a policy for identifying the creamy layer even from the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes so as exclude them from the benefit of affirmative action. In my view, only this and this a lone can achieve the real equality as enshrined under the Constitution," Justice Gavai concluded.

Judge Mithal dwelt on the difference between the varna and the caste systems, adding reservation is a medium for upliftment of the downtrodden but its execution revives casteism. He went on to suggest that quota should be limited only for the first generation or one generation of a family.

Why quota within quota matters

…and why the idea of a creamy layer is still deeply flawed, even if forward Dalits are better off today

The word reservation is like an arrow that pierces through the intellect of many without ever moving. In fact, the irony is that casteism was unleashed not as an arrangement, rather it spread like disease or bondage.

If an Abraham Lincoln polishes his own shoes, he doesn’t become untouchable. What happens is that American society chooses him as its leader, voluntarily. If there was any conflict there, it was racial, not ethnic.

After the Supreme Court’s decision on 1 August 2024 regarding the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe Mahadalits — be they the Valmiki/Mazhabi Samaj, the Musahar, the Madiga, the Chakkiliya or the Arunthathiyar — so many hitherto unimaginable forms appeared, the mind boggled.

There used to be a societal belief that if there was any dispute, go to a Darvesh scholar. Perhaps this is how the judiciary was formed, beginning with five panchas making a panchayat (a council of five). But today, the forward Dalit leaders and scholars ignore all decorum and stand in opposition to equality.

When they argue that Mahadalits should have studied and become equal to them, it seems as if the opponents of reservation in 1930–32 handed their daggers over to today’s forward Dalits and said, here, stab Ambedkar through the heart.

The question that naturally arises is this: given that all Dalits have been exploited and oppressed for years, how did some get ahead and some lag behind? The hon’ble Chief Justice of India D.Y. Chandrachud illustrated this with an example: the man pushing and shoving to get into an overcrowded train is bound to stop others from doing so.

Secondly, among the Dalits, the Ati or Mahadalits have also been formed by the mechanisms of the social system. Society has always kept sanitation workers at arm’s length. In the market, albeit by the wayside, the Dalit making or stitching shoes learned how to negotiate with both society and the market. That is how one got ahead and the other got left behind.

The condition of forward Dalits may well have improved a lot, yet society still doesn’t accept them as equals. Everyone is only too aware of this. Therefore, there should be no provision for the creamy layer. But for the upliftment of the Mahadalits, sub-classification in reservation is crucial.

This is not a warning, merely a description of the horrifying picture of the future that is in store. If the forward Dalit leaders and scholars continue to make such thoughtless statements, the chasm between them and the Mahadalits will widen so much, no one will be able to bridge it for ages.

The advance guard of the forward Dalits will be the first to face the consequences of this distance. While the forward Dalits may retain their toehold and stay where they are, chances of the Mahadalits slipping and falling further down are very real.

If you recall, whenever there has been an attack on reservation for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, the sanitation workers (Valmiki/Mazhabi) gave a befitting reply by coming out onto the streets. I remember 1981, when the movement against reservation started in Gujarat.

Dr. Chandola made Ludhiana railway station the centre of that movement. Many Dalit organisations battled on for many days but nothing happened. As soon as the Safai Karamchari Union of Ludhiana reached the protest site en masse, all the anti-reservation people were seen running away with their tails between their legs.

There are two ways to look at all this. One, Dalit unity is being broken. Second, a time will come when we will be incapable of facing any attack. In that case, all earlier efforts will seem meaningless. Think about it, all you intellectuals, writers and publishers.

Whenever you get a chance to go to Dalit conferences or releases of Dalit publications, you must have noticed that exploitation, suffering and atrocity are the main issues. There is anguish in the heart and fire in the words.

Then how is it that the living human who goes down into the sewer only to emerge as a corpse is not visible to the forward Dalits, especially the leaders and scholars on those forums? Because you have gone beyond governance and administration to become owners of business empires.

Sanitation workers, the Hela, Bansphor, Musahar, Valmiki, Dhanuk, Dom, Dumar Madiga, Chakkiliyar, Arunthathiyar have lost their steady jobs. What should have happened was that you should have come forward and extended a helping hand, not like the master of the universe but like the master of the ship.

By opposing the share of the most downtrodden Hela, Bansphor, Musahar, Valmiki/Mazhabi, Dhanuk, Dom, Dumar Madiga, Chakkiliyar, Arunthathiyar, you have proven that the germs of Manuvadi thought have deeply infected you.

Umpteen stories and Indian films used to show an elder brother sacrificing his entire youth in an effort to make the family stand on its own feet. Today, the Mahadalit castes, who took the blows on the streets for years, sense that the rest can’t tolerate their right to have a share in the reservation they fought for.

There are thousands, rather lakhs of private companies and factories being set up where there is no provision for reservation. What should have happened is that all of us should have come together, to compel all political parties and governments to give us a share in every apparatus that runs this land. Instead, we ourselves are pitted against our own.

Darshan Ratna Raavan is the chief of the Aadi Dharm Samaj (AADHAS), which fights for the dignity o

f Dalit identity

Chirag Paswan re-elected LJP (Ram Vilas) chief, pitches for caste census

Paswan, the Minister of Food Processing Industries, said the upcoming assembly elections in Haryana, Jammu Kashmir and Jharkhand were also discussed in the meeting

)

In Jharkhand, the party may contest the polls either with national alliance partner BJP or on its own, he said. (Photo: PTI)

Listen to This Article

+

+

The Rise of Dalit Cinema and Its Future

Harish S. Wankhede

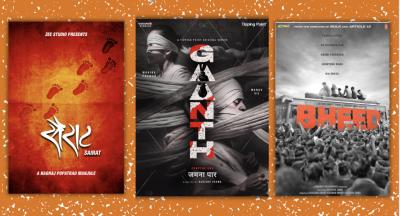

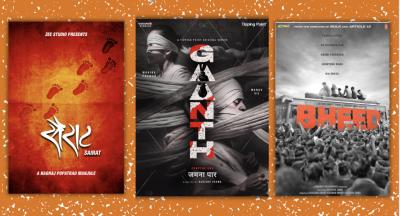

Aug 25, 2024Over the last 15 years we have witnessed a sudden arrival of films that have introduced Dalit characters as dignified protagonists. Posters of Sairaat (minimalmovieposters);Ghaanth, Bheed (IMDB).Advertisement

Posters of Sairaat (minimalmovieposters);Ghaanth, Bheed (IMDB).AdvertisementMarginalisation and neglect of certain social groups in democratic processes is injustice. Indian cinema for a long time has been dominated by the cultural and political interests of the social elites, disallowing any significant space to the voices and concerns of the socially marginalised communities, especially the Dalits. Though in the sphere of parliamentary democracy and in the arena of urban middle class establishments, the Dalit community has showcased their growing presence, the cultural industry has rarely reflected sensitively on their life experiences, social past and literary history.

AdvertisementAdvertisementSuch functionality of the film industry is undemocratic as it lacks social diversity and participation of vulnerable social groups as partners in creating cinematic art. Ironically, even in the alternative mode of ‘progressive, critical or Left-oriented’ cinema, questions of caste emerged only as a peripheral topic. The scant Dalit representation within parallel cinema was stereotypical, mostly portraying the community as powerless victims of Brahmanical exploitation (remember Satyajit Ray’s Sadgati 1981).

It is in the last 15 years that we have witnessed a sudden arrival of films that have introduced Dalit characters as dignified protagonists. These include a handful of films, particularly in Hindi (such as Masaan [2015], Bheed [2022], Shamshera [2022]), Marathi (Sairat [2016], Jayanti [2021]), and Tamil (Asuran [2021], Kala [2021], Kabali [2016]), some of which are directed by Dalit filmmakers like Nagaraj Manjule, Neeraj Ghaywan, and Pa Ranjith.

AdvertisementSuch representation breaks away from the stereotypical portrayal of the community as victims and powerless figured, as shown in the parallel cinema of 1970s, and elevates them to someone bestowed with powerful heroic abilities, like in Majhi, the Mountain Man (2015), and Sarpatta Parambarai (2021). These films have initiated a more nuanced Dalit representation on screen. By introducing a new narrative style, realistic characters and authentic social background, these films disturb the conventional practices of cinema. Like the alternative modes of film narratives, Dalit cinema too offers an ideological battle against the populist-masala cladded entertainment flicks and raises challenges against the powerful ideological values of the indomitable cultural industry.

Aug 25, 2024

Marginalisation and neglect of certain social groups in democratic processes is injustice. Indian cinema for a long time has been dominated by the cultural and political interests of the social elites, disallowing any significant space to the voices and concerns of the socially marginalised communities, especially the Dalits. Though in the sphere of parliamentary democracy and in the arena of urban middle class establishments, the Dalit community has showcased their growing presence, the cultural industry has rarely reflected sensitively on their life experiences, social past and literary history.

Such functionality of the film industry is undemocratic as it lacks social diversity and participation of vulnerable social groups as partners in creating cinematic art. Ironically, even in the alternative mode of ‘progressive, critical or Left-oriented’ cinema, questions of caste emerged only as a peripheral topic. The scant Dalit representation within parallel cinema was stereotypical, mostly portraying the community as powerless victims of Brahmanical exploitation (remember Satyajit Ray’s Sadgati 1981).

It is in the last 15 years that we have witnessed a sudden arrival of films that have introduced Dalit characters as dignified protagonists. These include a handful of films, particularly in Hindi (such as Masaan [2015], Bheed [2022], Shamshera [2022]), Marathi (Sairat [2016], Jayanti [2021]), and Tamil (Asuran [2021], Kala [2021], Kabali [2016]), some of which are directed by Dalit filmmakers like Nagaraj Manjule, Neeraj Ghaywan, and Pa Ranjith.

Such representation breaks away from the stereotypical portrayal of the community as victims and powerless figured, as shown in the parallel cinema of 1970s, and elevates them to someone bestowed with powerful heroic abilities, like in Majhi, the Mountain Man (2015), and Sarpatta Parambarai (2021). These films have initiated a more nuanced Dalit representation on screen. By introducing a new narrative style, realistic characters and authentic social background, these films disturb the conventional practices of cinema. Like the alternative modes of film narratives, Dalit cinema too offers an ideological battle against the populist-masala cladded entertainment flicks and raises challenges against the powerful ideological values of the indomitable cultural industry.

In 'Koothukaali', Exorcism is the Weapon of Choice to 'Cure' a Woman, and Silence is Her Response

In this context, the latest web series on Jio Cinema, Gaanth Chapter 1: Jamnaa Paar (2024), can be seen as another important addition that supplements the growing appeals to have more representation of Dalit characters on screen. The series offers a robust Dalit character who is engulfed in everyday urban tragedies bestowed upon her due to poverty, sexual and caste harassment and institutional negligence. Her track in the series adds to the other powerful stories available on various OTT platforms that have previously provided significant space to Dalit characters on screen as protagonists. This is a significant development in the history of Indian cinema as it has birthed a young Dalit genre that has the potential to democratise the film industry substantially. For the better future of this genre, a strong support base should be established by industry leaders, and the state should implement effective policy measures to ensure increased participation of Dalits in the film industry.

AdvertisementAlso read: Debate | The Return of the Dalit in the New Cinema of South India

Further, the proliferation of web based streaming services like Netflix and Amazon Prime have radically transformed the entertainment business in India. It offers exciting international content, introduces films that are critically acclaimed and also shows ‘original content’ filled with subtle anti-establishment voices. Stories with social sensitivity and political controversies have also gained a respectable space here, including the visible placement of caste and Dalit issues in the narratives.

Distinct from the conventional portrayals, a new set of Dalit characters have arrived that showcases them as the part of greater middle-class culture (Serious Men on Netflix) or as urban aspirants who wish to live a normal, dignified life (Paatal Lok 2020 (Amazon Prime). Importantly, the Dalit women characters in series like Maharani 2021 (Sony Liv), Aashram 2020 (MX Player) and Gilli Puchchi, an episode in the web anthology Ajeeb Daastaans 2021 (Netflix) further offered powerful Dalit women characters.

OTT and the making of the Dalit female protagonist

AdvertisementThe character of Sakshi Murmu (Monika Panwar) in Gaanth: Chapter 1 Jamnaa Paar substantiates the ongoing trend by offering significant screen presence to a Dalit female lead. Though the story revolves around the Burai mass suicide case, it reflects upon the dark underbelly of urban development, showcasing how the inhabitants are yet to be distanced from religious orthodoxy, conventional caste customs and illogical rituals. Modern institutions like hospitals and police departments are portrayed as corrupt, insensitive places that are distanced from the ideas of justice and fairness. In such a depressing portrayal of the city life, we see the struggle of a young medical apprentice, Murmu, who accidentally gets involved in a criminal case. She eventually showcases her hidden talent to solve the mystery and emerges as a parallel protagonist in the narrative.

We decode that Murmu is a medical student from the reserved category who faces incessant caste-based harassment and discrimination. However, the series also portrays her as a gifted, analytical mind, curious to unearth the facts related to a tragic incident of homicide murders. She often ignores the everyday bouts of caste harassment but on occasions also demonstrates heroic impulses to register her protest against the perpetrators. Such nuanced portrayal suggests that though the caste system has not loosened its discriminatory grip over the Dalit community, they have this innate individual ability to escape the caste prison and perform as conscious and moral beings. Murmu’s honest determination to resolve the mystery successively overcomes the social and institutional barriers.

In earlier narratives (such as Gilli Puchchi), Dalit characters are depicted as being affected and burdened by Brahmanical patriarchy. However, they also exhibit the capacity and courage to emerge as heroic figures. This represents a substantive shift from the portrayal in parallel cinema, where Dalit women were often depicted as impoverished and perpetually exploited, as seen in Gautam Ghosh’s Paar (1984), or violated and raped by dominant caste elites with near impunity in Nishant (1975) and Damul (1985), and lacking the agency to challenge such atrocities. The current scenario suggests that social control and prejudices against Dalit bodies are subtly receding, allowing Dalit characters, including women, to be presented as liberated individuals.

In another example, we see Pallavi Manke (Radhika Apte), in the web-series Made in Heaven, a proud Dalit professor, working at an Ivy League university, and has no hesitation to flag her ‘ex-Untouchable’ identity. Though she is marrying a sensitive and progressive Indian-American lawyer, she faces social burdens and anxieties when she offers to add a Buddhist ritual to her marriage ceremony. The story is beautifully woven, representing the social principles that Ambedkar wanted to establish in India’s social life. Like these stories, Murmu is also showcased as a protagonist with abilities that can challenge the conventional patriarchs and emerge as an inspirational character in the narratives.

AdvertisementAlso read: The Dalit Person in Mainstream Indian Cinema

Such characters have certainly sown the seeds for the emergence of a Dalit genre in Indian cinema, though it is still in its nascent stage. There is a growing possibility that this young yet impressive presence of Dalit characters could soon develop into an influential genre. Like other significant genres – parallel cinema, Muslim social, or the recent Hindutva-based films – Dalit cinema has yet to make its mark on the film industry. For Dalit characters to become significant in mainstream movies and on OTT platforms, a radical shift in the social psyche of filmmakers is required.

Future of the Dalit cinematic genre

AdvertisementDalit cinema has surely initiated a reform as more creative artists from marginalised social groups join the film industry to showcase their stories. These narratives offer organic cinematic content without diluting the entertainment quotient. Though many of the films have impressive box-office success – like Sairat, which is the biggest blockbuster in Marathi cinema till date – this genre is yet to build a substantive mass following and has little power to radicalise the popular and conventional patterns of film making. It has initiated a steady, if slow, movement for a much-needed democratisation of the film industry. However, without the support of the conventional leaders of the industry, it will remain a marginalised genre.

Dalit cinema is inspired by the fascinating success of Black American film fraternity and other minority groups that argue for diversity and social harmony in the cultural industry. It is equally important that the Indian cinema industry learn from Hollywood’s fascinating social experiences and cultural innovations that has made Blacks, Asians, Jews and other minorities not only a significant part of cinema narratives, but also as influential artists, creators and producers. Given India’s own diversity in terms of culture and caste, it is essential for industry leaders to explore how cultural institutions can become more democratic and representative of these social nuances. Representing the people that have historically remained outside the purview of mainstream cultural practices will showcase that the Indian film industry cherishes liberal-democratic credentials and it is not an exclusive domain of few rich classes and social elites.

It is an appropriate time for the film fraternity to recognise and collaborate with the outstanding cinematic works of artists and producers belonging to the socially marginalised communities, elevating them as an inspiration for the new generation. New cultural festivals, public institutions and policy frameworks by the state are required to promote the culture and talent of diverse social groups that are often marginalised in mainstream discourse on cinema and art. It is essential to create new platforms and for existing popular culture establishments to adapt in order to connect producers, artists, and technicians from Dalit backgrounds for future collaborations.

AdvertisementFurthermore, it is crucial for Dalits to also enter the film industry as producers, technicians, and directors to showcase their stories and talents more prominently. However, both of these possibilities face numerous obstacles. It is high time that the emerging Dalit genre be recognised as part of the reformist cinema movement, driven by a vision that cinema has a critical role in demonstrating social diversity and promoting the values of social justice. Such cinema would create an independent platform for artists, creators, and film enthusiasts to build and celebrate an alternative cultural space, highlighting the dignity and diversity of historically marginalised social groups and integrating them into the cultural industry.

Harish S. Wankhede is Assistant Professor, Center for Political Studies, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.

BJP committed to welfare of Dalits: Union minister Arjun Ram Meghwal

BJP committed to welfare of Dalits: Union minister Arjun Ram Meghwal

https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/bjp-committed-to-welfare-of-dalits-union-minister-arjun-ram-meghwal/articleshow/112813983.cmsDownload the TOI app now:https://timesofindia.onelink.me/mjFd/toisupershare

.......

In this context, the latest web series on Jio Cinema, Gaanth Chapter 1: Jamnaa Paar (2024), can be seen as another important addition that supplements the growing appeals to have more representation of Dalit characters on screen. The series offers a robust Dalit character who is engulfed in everyday urban tragedies bestowed upon her due to poverty, sexual and caste harassment and institutional negligence. Her track in the series adds to the other powerful stories available on various OTT platforms that have previously provided significant space to Dalit characters on screen as protagonists. This is a significant development in the history of Indian cinema as it has birthed a young Dalit genre that has the potential to democratise the film industry substantially. For the better future of this genre, a strong support base should be established by industry leaders, and the state should implement effective policy measures to ensure increased participation of Dalits in the film industry.

Also read: Debate | The Return of the Dalit in the New Cinema of South India

Further, the proliferation of web based streaming services like Netflix and Amazon Prime have radically transformed the entertainment business in India. It offers exciting international content, introduces films that are critically acclaimed and also shows ‘original content’ filled with subtle anti-establishment voices. Stories with social sensitivity and political controversies have also gained a respectable space here, including the visible placement of caste and Dalit issues in the narratives.

Distinct from the conventional portrayals, a new set of Dalit characters have arrived that showcases them as the part of greater middle-class culture (Serious Men on Netflix) or as urban aspirants who wish to live a normal, dignified life (Paatal Lok 2020 (Amazon Prime). Importantly, the Dalit women characters in series like Maharani 2021 (Sony Liv), Aashram 2020 (MX Player) and Gilli Puchchi, an episode in the web anthology Ajeeb Daastaans 2021 (Netflix) further offered powerful Dalit women characters.

OTT and the making of the Dalit female protagonist

The character of Sakshi Murmu (Monika Panwar) in Gaanth: Chapter 1 Jamnaa Paar substantiates the ongoing trend by offering significant screen presence to a Dalit female lead. Though the story revolves around the Burai mass suicide case, it reflects upon the dark underbelly of urban development, showcasing how the inhabitants are yet to be distanced from religious orthodoxy, conventional caste customs and illogical rituals. Modern institutions like hospitals and police departments are portrayed as corrupt, insensitive places that are distanced from the ideas of justice and fairness. In such a depressing portrayal of the city life, we see the struggle of a young medical apprentice, Murmu, who accidentally gets involved in a criminal case. She eventually showcases her hidden talent to solve the mystery and emerges as a parallel protagonist in the narrative.

We decode that Murmu is a medical student from the reserved category who faces incessant caste-based harassment and discrimination. However, the series also portrays her as a gifted, analytical mind, curious to unearth the facts related to a tragic incident of homicide murders. She often ignores the everyday bouts of caste harassment but on occasions also demonstrates heroic impulses to register her protest against the perpetrators. Such nuanced portrayal suggests that though the caste system has not loosened its discriminatory grip over the Dalit community, they have this innate individual ability to escape the caste prison and perform as conscious and moral beings. Murmu’s honest determination to resolve the mystery successively overcomes the social and institutional barriers.

In earlier narratives (such as Gilli Puchchi), Dalit characters are depicted as being affected and burdened by Brahmanical patriarchy. However, they also exhibit the capacity and courage to emerge as heroic figures. This represents a substantive shift from the portrayal in parallel cinema, where Dalit women were often depicted as impoverished and perpetually exploited, as seen in Gautam Ghosh’s Paar (1984), or violated and raped by dominant caste elites with near impunity in Nishant (1975) and Damul (1985), and lacking the agency to challenge such atrocities. The current scenario suggests that social control and prejudices against Dalit bodies are subtly receding, allowing Dalit characters, including women, to be presented as liberated individuals.

In another example, we see Pallavi Manke (Radhika Apte), in the web-series Made in Heaven, a proud Dalit professor, working at an Ivy League university, and has no hesitation to flag her ‘ex-Untouchable’ identity. Though she is marrying a sensitive and progressive Indian-American lawyer, she faces social burdens and anxieties when she offers to add a Buddhist ritual to her marriage ceremony. The story is beautifully woven, representing the social principles that Ambedkar wanted to establish in India’s social life. Like these stories, Murmu is also showcased as a protagonist with abilities that can challenge the conventional patriarchs and emerge as an inspirational character in the narratives.

Also read: The Dalit Person in Mainstream Indian Cinema

Such characters have certainly sown the seeds for the emergence of a Dalit genre in Indian cinema, though it is still in its nascent stage. There is a growing possibility that this young yet impressive presence of Dalit characters could soon develop into an influential genre. Like other significant genres – parallel cinema, Muslim social, or the recent Hindutva-based films – Dalit cinema has yet to make its mark on the film industry. For Dalit characters to become significant in mainstream movies and on OTT platforms, a radical shift in the social psyche of filmmakers is required.

Future of the Dalit cinematic genre

Dalit cinema has surely initiated a reform as more creative artists from marginalised social groups join the film industry to showcase their stories. These narratives offer organic cinematic content without diluting the entertainment quotient. Though many of the films have impressive box-office success – like Sairat, which is the biggest blockbuster in Marathi cinema till date – this genre is yet to build a substantive mass following and has little power to radicalise the popular and conventional patterns of film making. It has initiated a steady, if slow, movement for a much-needed democratisation of the film industry. However, without the support of the conventional leaders of the industry, it will remain a marginalised genre.

Dalit cinema is inspired by the fascinating success of Black American film fraternity and other minority groups that argue for diversity and social harmony in the cultural industry. It is equally important that the Indian cinema industry learn from Hollywood’s fascinating social experiences and cultural innovations that has made Blacks, Asians, Jews and other minorities not only a significant part of cinema narratives, but also as influential artists, creators and producers. Given India’s own diversity in terms of culture and caste, it is essential for industry leaders to explore how cultural institutions can become more democratic and representative of these social nuances. Representing the people that have historically remained outside the purview of mainstream cultural practices will showcase that the Indian film industry cherishes liberal-democratic credentials and it is not an exclusive domain of few rich classes and social elites.

It is an appropriate time for the film fraternity to recognise and collaborate with the outstanding cinematic works of artists and producers belonging to the socially marginalised communities, elevating them as an inspiration for the new generation. New cultural festivals, public institutions and policy frameworks by the state are required to promote the culture and talent of diverse social groups that are often marginalised in mainstream discourse on cinema and art. It is essential to create new platforms and for existing popular culture establishments to adapt in order to connect producers, artists, and technicians from Dalit backgrounds for future collaborations.

Furthermore, it is crucial for Dalits to also enter the film industry as producers, technicians, and directors to showcase their stories and talents more prominently. However, both of these possibilities face numerous obstacles. It is high time that the emerging Dalit genre be recognised as part of the reformist cinema movement, driven by a vision that cinema has a critical role in demonstrating social diversity and promoting the values of social justice. Such cinema would create an independent platform for artists, creators, and film enthusiasts to build and celebrate an alternative cultural space, highlighting the dignity and diversity of historically marginalised social groups and integrating them into the cultural industry.

Harish S. Wankhede is Assistant Professor, Center for Political Studies, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.

Comments

Post a Comment