11.11.2025...Sivaji's..Untouchables News in India.by Team Sivaji.9444917060.follow us in all Social Media.

Asothar police accused of assaulting a Dalit family: Woman suffers head injury, station in-charge calls allegations baseless

Police in Fatehpur's Asothar police station area have been accused of assaulting women and girls from a Dalit family. The incident came to light after a video went viral on social media, allegedly showing two girls and two women being assaulted by policemen inside the police station premises.

It is alleged that 10 to 12 policemen kicked, punched, and beat a young woman with belts, both inside and outside the police station, resulting in serious head injuries. The medical report also documented the injuries.

Family members of the victim, Deepika, stated that the incident stemmed from a dispute over the payment for a pig. Deepika's elder mother had sold a pig to a trader, and an argument ensued over the payment. The businessman filed a complaint at the Asothar police station, following which a police team arrived at Kauder village and summoned the family. The family alleges that upon arriving at the police station, the policemen misbehaved with the women and their daughters and then began beating them inside.

According to the victim, Deepika, after the beating, the police issued a challan under Section 151. Despite suffering a serious head injury, she was not given a medical examination. The family reported that Deepika's health is continuously deteriorating and she is vomiting. The woman's wedding is scheduled for November 22nd, which is worrying the family.

Asothar police station in-charge Abhilash Tiwari presented his side of the story. He stated that people who had come to buy pigs were assaulted and injured. A case has been registered in this regard, and some of the accused have been detained and presented in court, while one is still absconding. The station in-charge alleged that false videos and photographs are being circulated against the police to protect the absconding accused. He clarified that the police did not assault anyone and all the allegations are baseless.

Amar Kesharwani

Courtesy : Hindi News

Bihar Elections: If 18% of Dalits support… you’ll win the crown. Find out who’s in the mood?

Bihar Politics: Campaigning for the second and final phase of the Bihar Assembly elections has concluded. All eyes are now on Dalit and Muslim voters, who are considered to hold the key to power.

Bihar Assembly Elections: Campaigning for the second and final phase of the Bihar Assembly elections has concluded. All eyes are now on Dalit and Muslim voters. According to analysis, the key to the mandate lies in the hands of 18% Dalit voters, who have the power to swing the outcome in nearly 100 seats.

This phase also holds clues to the future political future of the Muslim community, which has a significant presence in three dozen seats, including Seemanchal. The situation this time is slightly different from the previous election. VIP, which supported the NDA last time, is now with the Grand Alliance, while Chirag, who contested the elections on his own, is working to strengthen the NDA this time.

Why is PK trying his best?

Beyond the opposition Grand Alliance, the Jan Suraj Party, following the AIMIM, is also striving to establish itself as the leader of Muslims. In a close contest, the NDA narrowly reached the magic majority mark by winning 17 more seats than the Grand Alliance.

A 1.6% Vote Shift

In the last election, the NDA received 1.6% more votes than the Grand Alliance. This lead helped it win 66 seats compared to the Grand Alliance’s 49. The NDA secured a significant lead in Anga Pradesh, Tirhut, and Mithila, while the RJD secured a significant lead in the Magadh region. In Seemanchal, the close contest and the presence of the AIMIM gave the NDA a slight advantage.

The Dalit community is the most important constituency in this phase. Of the Dalit community, which constitutes 18% of the total vote share, 13% are Mahadalits (of which 2.5% are Musahars) and 5% are Paswan (Dusadh). There are approximately 100 seats where the voter population of this community is between 30,000 and 40,000 per seat.

Chirag came and Sahni left.

JDU directly lost 22 seats due to Chirag contesting the elections on his own. The BJP and political pundits believe that the alliance between Chirag and Jitan Ram Manjhi will consolidate 7.5% of the Paswan and Musahar community votes in favor of the NDA.

Muslims are hoping for new leadership.

For decades, RJD’s powerful leaders were the face of Muslim politics in Seemanchal. Now, there is a clear anxiety among Muslims about new leadership. The AIMIM, which won five Muslim-dominated seats in Seemanchal in the last election, has linked the Mahagathbandhan’s failure to field a deputy CM candidate to an insult to the community.

Furthermore, the newly formed Jan Suraj Party, which is contesting this election, is also striving to establish itself as a leader of Muslims. The AIMIM has fielded Muslim candidates in all Muslim-dominated seats. The Jan Suraj Party has also fielded candidates from the same community in Muslim-majority seats.

By Abhishek Singh

Courtesy: Hindi News

‘You Have No Right to Drink With Me’: Dalit Man Stabbed and Beaten With Stone by Friend in MP’s Gwalior

A disturbing case of caste-based violence has been reported from Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh, where a drunken argument between two friends turned into a assault.

According to the police, Balveer Valmiki and Vijay Sharma, both residents of Mahavir Colony, were friends. On Sunday afternoon, Vijay allegedly invited Balveer to drink near Badanpura on Tighra Road. The two consumed alcohol together, but as evening fell, an argument erupted between them.

Vijay reportedly began hurling casteist slurs, saying, “You belong to a lower caste; you have no right to drink with me.” When Balveer protested, Vijay’s anger escalated he allegedly pulled out a knife and stabbed Balveer in the neck. When the victim collapsed, bleeding heavily, Vijay picked up a large stone and struck him on the head before fleeing the spot.

Balveer remained unconscious throughout the night until passersby discovered him the next morning and alerted the police. He was rushed to a nearby hospital, where doctors said his condition is now stable but that he sustained deep wounds to his neck and skull.

Based on Balveer’s statement, police registered a case and launched a search operation. Acting on the directions of Station Officer Ratnambar Shukla, a team arrested the accused Vijay Sharma near his home.

This is not an isolated incident. In October, a Dalit driver from Gwalior had alleged that three men kidnapped, assaulted, and forced him to drink urine in Bhind district. Just days earlier, another Dalit youth was reportedly urinated on in Katni for protesting against illegal mining.

According to the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) 2023 data, crimes against Scheduled Castes continue to rise nationwide, with 57,789 cases registered last year, marking an increase from 2022. Madhya Pradesh recorded 8,232 such cases, placing it among the top three states for caste-related crimes, after Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan.

Courtesy : TOP

Chhatarpur - A long-standing land dispute in Chhatarpur district of Madhya Pradesh took a violent and shocking turn when a woman was allegedly tied up and brutally beaten in a field. The incident, which occurred on Friday in Gorakhpura village under the Bhagwa police station limits, has sparked widespread outrage after videos of the assault went viral on social media.

The conflict is between the Sen and Dwivedi families over a 4.796-hectare plot of land (Khasra No. 1219). The legal title to this land is currently sub-judice, pending a decision in the court of the Upper Collector and SDM of Bada Malhera.

According to the victim, Sahodara Sen, the incident unfolded on Friday morning around 9 AM when members of her family went to the field to plough it. They were confronted by Jagdish Singh Dwivedi and his sons—Captain, Gaurav, and Sonu Dwivedi.

Sahodara Sen stated in her police complaint, "I only said that since the case is in court, no one should plough the land until a verdict is reached. Upon this, they attacked me, tied my hands, legs, and mouth with a rope, and mercilessly beat me with kicks and punches." The accused then allegedly fled the scene.

Two videos have emerged, bringing the incident to light. Video 1 shows Sahodara Sen with her hands and feet bound in the field. Video 2 Shows a man arriving on a bike and verbally abusing the woman and her family.

The victim's family managed to free her and recorded the entire episode before approaching the police outpost in Ghuwara to file a formal complaint.

Ranchi- The Jharkhand government has invited applications from Scheduled Tribe (ST) students for free residential coaching to prepare for the NEET and JEE entrance examinations under the “Jharkhand Scheduled Tribe Education Upliftment Programme,” a government statement said. The scheme, launched by the Department of SC, ST, Minority and Backward Classes Welfare, aims to support meritorious tribal students aspiring to become doctors and engineers by removing financial barriers to quality coaching.

Patna: In the cracked, sun-scorched hamlets of Bihar’s Gangetic plains, where monsoon floods swallow entire seasons of hope and the earth bakes hard enough to blister bare feet, the Musahar community has survived for centuries on the thinnest edge of existence.

Their very name means rat-eaters, and it carries the weight of a stigma older than the republic. For generations, they survived by feeding on field rats from burrows with smoldering straw, roasted the meager catch over cow-dung fires, and divided the meal among children whose bellies bloated from chronic hunger.

This was never tradition. It was desperation. Over 96 percent of them own no land. Ninety-two percent labor on others’ fields for wages that disappear before the next sunrise. The 2011 Census recorded their literacy at 9.8 percent, which is lower than any Dalit group in India, with female literacy scraping 1 percent. In some villages, 85 percent of children showed signs of severe malnutrition. Malaria, kala-azar, and tuberculosis stalked households the state barely registered. Yet in one quiet corner of Patna, a retired policeman’s defiance has begun to rewrite this inheritance of despair.

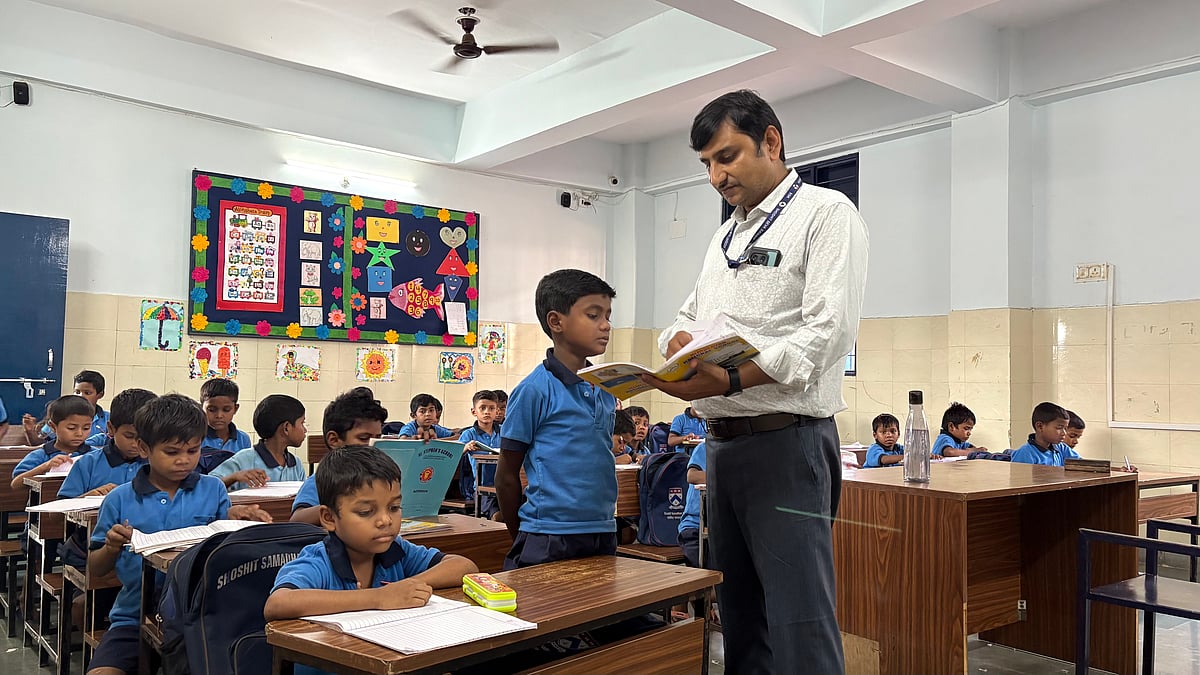

Jyoti Kumar Sinha, a Padma Shri–honored IPS officer, never forgot the Musahar boy he saw naked and shivering on a winter night in 1980s Patna. In 2005, the year he retired, Sinha sold his Delhi flat, returned to Bihar, and founded Shoshit Seva Sangh. His new battlefield: a school.

Shoshit Samadhan Kendra (SSK) opened with four boys. Today, 550 Musahar children, first-generation learners from all 38 districts of Bihar, study and live under one roof, entirely free. Uniforms, textbooks, medical care, three meals a day, even soap and toothbrushes: every paisa comes from donors who believe one educated child can torch an entire tola’s darkness.

Step through the iron gates on Shivalaya Road, and the transformation slams like a cool wind. Boys in school uniforms sprint across separate playgrounds, one for hockey, another for volleyball, coached by four full-time sports teachers. In the robotics lab, a Class 8 student solders circuits while explaining neural networks in fluent English. “We run AI and robotics workshops now,” says Principal Sushma Pandey, 44, who abandoned a cushy private-school job to mother these children. “Teaching them is different. It gives us inner satisfaction. I treat them like my own children.”

She distributes special concept notes, knowing many arrive unable to grip a pencil. Within a year, they grow and learn so much they could never have if this school wasn’t there. The numbers are only half the story. Since 2018, SSK passouts have scattered like seeds in rich soil. One student went on to become the first Musahar to earn an LLB. He now argues cases in Patna High Court. Another student, who was the son of a Phulwari Sharif brick-kiln worker, won the Dyer Fellowship to study in the US. Two students, childhood friends from Gopalganj, secured scholarships at Ashoka University. One alumnus serves in the Bihar bureaucracy; another teaches at a Delhi NGO.

They return during vacations, speaking of the change in their living standards and their “inclusion in the mainstream” and their “acceptance” in the society. Village elders who once feared that the school staff could be people involved in kidney-harvesting rumors and believed in rumpus, now queue at admission camps, begging for an LKG seat in this school. For all they know, if one child of theirs gets to study here, he will uplift their family for generations to come.

Rajeev Kumar, Chief Project Administrator, has witnessed this miracle for 18 years. “People used to ignore them or feel uneasy even talking to Musahars,” he says. “But here, they speak English, wear clean clothes, eat nutritious food, and live in a good environment. When they go home, they initiate change in terms of teaching their siblings, insisting on hygiene, and refusing early marriage.”

Indian Christians mark Dalit Liberation Sunday, seek end to caste bias

In this file photo, Indian Dalit Christians and Muslims join a protest rally demanding equal rights. (Photo: AFP)

Christians across India set aside denominational differences to mark Dalit Liberation Sunday on Nov. 9, pledging solidarity with marginalized Dalit communities and renewing calls to end caste-based discrimination in the Church and society.

With special prayers and Sunday liturgy, Christians prayed to end the injustice to the socially poor Christians from Dalit groups, said Father Vijay Kumar Nayak, secretary of the Indian Catholic bishops’ Office for Dalits and Lower Classes.

Seminars, debates, meetings, and protest programs were also organized in some parishes as part of the observance to raise broader awareness in society about the discrimination suffered, Kumar said.

The annual observance — endorsed by the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of India (CBCI) and the National Council of Churches in India (NCCI), a forum of Protestant and Orthodox churches — has been held since 2007 to support Dalit Christians, who often face exclusion both within the Church and in wider society.

The observance “is a call to the whole Christian community to renew our faith and to stand with the vulnerable Dalits in society,” said Father Vijay Kumar Nayak, secretary of the CBCI Office for Dalits and Lower Classes.

“Despite a legal ban, the caste system remains deeply embedded in our society, shaping how we relate to one another, how we worship, and how we live out our Christian faith. It tears apart the Body of Christ and silences the voices of the poor,” he told UCA News.

This year’s theme — “The Jubilee of Hope Begins at the Margins” — coincides with the Church’s Year of Jubilee, emphasizing that God’s work of salvation “always begins with the poor, the excluded, and the oppressed,” Nayak added.

Under India’s constitution, socially poor Dalit and tribal people—officially called Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes--receive benefits in education, employment, and political representation.

However, a 1950 Presidential Order excluded Dalits who converted to Christianity or Islam from these privileges, arguing that those religions do not recognize caste. Sikhs and Buddhists were later included, but Dalit Christians and Muslims remain excluded despite decades of advocacy.

Dalits, historically known as “untouchables,” make up about 201 million of India’s 1.4 billion people, while Church sources estimate that about 60 percent of India’s 25 million Christians come from Dalit or tribal backgrounds.

Rights activists and community leaders say Dalit Christians continue to face discrimination within Church structures, including denial of equal participation and leadership roles.

Asher Noah, secretary of the NCCI’s Dalit and Tribal Concerns department, said Indian churches have adopted a “zero-tolerance policy” toward caste discrimination.

“Christians today recognize that caste is not just a social issue but one that strikes at the heart of our faith and the gospel message,” Noah said.

“No one can serve Christ and caste — the practice of caste is sin, and untouchability is crime.”

Letter from Rome every week.

Robert Mickens has been reporting and commenting on the Vatican and the Catholic Church the past four decades through his celebrated weekly Letter from Rome.

Mickens arrived in Rome in 1986 to study theology at the Jesuit-run Pontifical Gregorian University. And he has remained in the Eternal City ever since. His voice, shaped by decades in Rome, continues to inform and inspire readers around the world.

UCAN News is proud to present Micken' Letter from Rome commentaries every week.

https://www.deccanchronicle.com/southern-states/andhra-pradesh.

Dealing with Quotas in India's Private Universities

Reporter

November 10, 2025 | 07:36 am

Caste-based reservation is back on India’s political landscape. Some national political parties are clamouring for quotas for students seeking entry to the country’s private colleges and universities.

In early April, when the Congress strongly backed quotas for students from socially and economically marginalised communities, there was little or no dispute among political parties over an issue that has been hanging fire for almost ten years.

Four months later, the party reiterated its stand, saying that it was “no longer possible” to ignore the demand for reservation for Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and Other Backward Castes.

In the past, the Supreme Court has passed judgements on reservations in “private unaided institutions” and declared them constitutionally permissible. But private universities are not bound by law to provide reservations to students from economically weaker sections of the population.

Recently, a parliamentary committee, headed by a Congress Member of Parliament, Digvijaya Singh, recommended that a legislation was imperative for making quotas – 27 percent for OBCs, 15 percent for SCs and 7.5 percent for STs – in private higher educational institutions.

The panel expressed concern over the low enrolment of students from economically depressed sections in private universities with Institution of Eminence status. High tuition fees in private institutions have kept them off limits for students from marginalised communities. In 2022-23, there was a high dropout rate amongst SC/ST students from the IITs compared to other undergraduate students from the general category. Reports say that it will need four centuries for SC-ST candidates to clear IIT entrance tests without the support of quotas.

An IIT-Kanpur alumnus and founder of the Global-IIT Alumni Support Group contended that the government should have more targeted policies for mainstreaming SC, ST and OBC students. The blanket policy of reserving seats for these communities caused more harm than it should have, the support group founder said. It affected their performance, and the level of psychological pressure a quota student goes through could not be ignored.

A December 2023 Education Ministry report pointed to more than 13,000 SC, ST and OBC students quitting their degree programmes at some of the IITs and top-tier management schools.

Social discrimination

They cited caste discrimination on university campuses as one of the major reasons. A suicide involving a PhD student at the University of Hyderabad highlights the prevalence of discrimination in educational institutions where Dalit students face biases that range from delays in transferring scholarship to allocation of PhD supervisors.

While quotas were implemented in the 1970s and 1980s for SC and ST categories, the government reserved seats for OBC and EWS (economically weaker sections) in the 2000s. But the reality today remains grim for reserved category students.

A 2023 report by the All India Survey on Higher Education says that the total enrollment of SC and ST students in higher education stood at 14.25 percent and 5.5 percent, respectively. This is way below the national average of 26.3 percent. Most of these students are enrolled in undergraduate programmes across India. Of the 14.25 percent, over 13.5 lakh students (about 52 percent from the reserved categories) dropped out of their respective programmes either due to academic pressure or harassment on campus by peers and administration.

The University Grants Commission launched a programme to bridge the gap between SC/ST and general category students. It has taken measures such as mandated teaching courses on social exclusion for students pursuing MA and PhD, workshops, seminars, empirical studies on social exclusion and building data banks for comparative studies to raise awareness and sensitivity towards issues such as marginalisation.

Students from all socioeconomic groups prefer government colleges and universities. Every year, students appear for CUET examinations after taking their respective board level exams with the hope of qualifying for public universities, despite upgraded facilities in private academic institutions.

Rather than adding another layer of reservation, it will make sense to examine what the public universities lack, and the reasons students from backward communities drop out.

Many students from marginalised backgrounds confront several challenges, including getting involved with household chores after they clear high school, leaving them with little time to prepare for college or avail private tuition.

With such disadvantages, they remain in no position to compete with students from general categories. In such a situation, the government could take steps to assist students from economically and socially weak sections while they are in school. Establishing neighbourhood coaching centres could help children living in slums.

There are other challenges. By the time the students enter colleges and universities, they are also expected to earn, especially those who belong to low-income families. This contributes to the high dropout rates.

When there are little or no job guarantees for high school graduates, irrespective of the social categories they belong to, the future becomes even more uncertain, especially when the informal sector is a poor alternative.

A 2022 report by the Centre for Policy Research in Higher Education pointedly said that graduates from lowly-placed educational institutions, which attract students from low socioeconomic backgrounds, find it difficult to be employed.

Broad-based policy

Most private university students belong to families in the high-income category. While some private colleges do enroll students from low-income families, they have very few resources to help these students move up the social ladder.

American non-selective private colleges that admit students from the bottom quintile have very poor resources, financially and academically. The lowest income students in such colleges have only a 7 percent chance of making it to at least the upper-middle class by the time they reach their early 30s.

In India, privatisation of education has definitely improved access, but simultaneously, it has deepened commercialisation, compromised quality and bypassed regulation. The non-selective private universities only attract poor quality students from all socioeconomic categories, which does not improve upward mobility for marginalised sections.

It was reported in 2016 that only 42 percent of Dalit households had at least one literate member, as against 68 percent of non-Dalit households. Students from reserved categories, who do not get proper education, return to the same vicious cycle of poor living conditions and education and unemployment.

Additionally, these reserved category students face the risk of severe reverse discrimination and segregation in private universities. Given their family backgrounds, they are unable to match the lifestyles of their fellow classmates. This can lead to toxic resentment on both sides.

Many general category students hold the grudge that they do not get the opportunity to enrol in elite public universities because of reserved quotas, whereas students from reserved categories qualify with only 45 percent marks.

In these circumstances, the government could adopt a more broad-based policy, which encompasses continuing reservation for socially and economically backward students while also giving equal weightage to merit-based admission. As in South Africa, a rights-based approach could be adopted to engender a culture that respects diversity.

The government could take serious steps aimed at preparing students from marginalised communities to compete in exams such as JEE, CUET, NEET, UPSC etc.

A policy must be adopted to prohibit coaching centres from charging exorbitant fees that middle-income families are unable to afford. Such coaching centres could be directed to enroll SC, ST and OBC students so their training is at par with their general category counterparts.

Social equity would be achieved when students from marginalised and general categories are on an even keel.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.

*) DISCLAIMER

Articles published in the “Your Views & Stories” section of en.tempo.co website are personal opinions written by third parties, and cannot be related or attributed to en.tempo.co’s official stance.

A Mountain To Break: Is Dalit Upliftment Just A Pipe Dream In Bihar?

The stories of Dashrath Manjhi and Laungi Bhuiyan reveal a deeper pattern of how Bihar’s Dalits remain confined to announcements and symbolism rather than tangible progress

Dalits, who make up 20 per cent of Bihar’s population, hold just 1.3 per cent of government jobs, a stark reminder of structural exclusion.

Before the 1970s, Dalit voters largely supported the Congress. Later, they shifted toward regional and caste-based parties, first aligning with Lalu Prasad Yadav in the 1990s and then with Ram Vilas Paswan.

When Nitish came to power in 2005, he fragmented Dalits further by carving out the Mahadalit category to politically consolidate the most marginalised castes, including the Manjhis

For over two decades, Bihar’s political class has borrowed the legacy of Dashrath Manjhi, the “Mountain Man” who literally carved through a mountain of stone with a hammer and chisel to mine votes from memory. The name of the man who inspired the Bollywood film Manjhi–The Mountain Man, is invoked at rallies, his image is flashed on banners and promises are made in his honour.

Chief Minister Nitish Kumar once claimed to be so moved by Manjhi’s feat that he offered him his own chair, a gesture meant to bridge the symbolic distance between ruler and ruled. Union Minister Jitan Ram Manjhi, from the same community, went even further, calling Dashrath his “relative”. But when the Mountain Man died in 2007 and his son asked for nothing more than a small permanent home, the responses from both leaders revealed what truly lies beneath the surface of Bihar’s politics: empathy that ends at the microphone.

When Bhagirath Manjhi, Dashrath’s son, appealed to Nitish, saying: “You’ve glorified my father’s name across Bihar; at least help us build a house to live in,” Nitish replied dryly, “Did you not get an Indira Awas (a housing grant)?”

Later, Bhagirath approached Jitan Ram with the same plea, “Please help build us a two-room house.” The response was equally telling: “You already have a mud house, don’t you? What’s the problem living in that?”

The Forgotten Family of the Mountain Man

Back in 1992–93, Dashrath Manjhi received Rs 15,000–Rs 20,000 under the Indira Awas Yojana. With that, he built a mud house that soon collapsed during the monsoon. He continued to live amid the ruins for years, as did his son Bhagirath, his daughter-in-law and five grandchildren until just a few months ago. But it raises the question, why did this recognition come only during election season, even though Dashrath’s feat had been celebrated worldwide more than a decade earlier?

This story reveals a deeper pattern of how Bihar’s Dalits remain confined to announcements and symbolism rather than tangible progress. When Nitish came to power in 2005, he reclassified Dalit castes (except the Paswans) as Mahadalits, promising targeted upliftment. Yet among these groups, the Manjhi community continues to wait endlessly for change.

Two days before the first phase of voting, when we reached Dashrath Manjhi’s village around 8 pm, his granddaughter Anshu Kumari, 30, sat outside under a thatched verandah with her five children. Some wore torn clothes; others had none. “I studied up to intermediate (level),” Anshu said. “Because of my grandfather, the whole world knows Gahlour Hill. He cut through a mountain to build a road; the government collects tax from that road but gives nothing to the man who built it.” She went on: “Hospitals, roads and memorials are named after my grandfather, but our family got nothing—not even a job or a home.” When Rahul Gandhi told her to raise her children to make her grandfather proud, she asked in return, “Where will I educate my children from?”

Dashrath Manjhi’s tale begins with love and loss. Born on January 14, 1934, in Gahlour village, Gaya district, he was neither educated nor wealthy. But when his wife, Falguni Devi, fell ill and died because the nearest hospital lay beyond a mountain, something inside him ignited. He vowed to carve a path through the mountain so that no one else would suffer as he did. For 22 years (1960–1982), armed only with a hammer and chisel, he toiled day after day. Villagers mocked him, but he would simply smile and say: “The mountain will fall one day.” Eventually, he carved a 110-metre-long, 9-metre-wide, 7.6-metre-deep road, connecting Gahlour to the outside world.

But symbolism could not feed his family. As Bhagirath recalls, “When my grandfather was dying, Nitish Kumar asked what he could do for our family. He said, ‘Why should I ask for one son, when the whole community is my family?’” The son adds, “If the government couldn’t do anything for his family, imagine what it has done for the Manjhi community at large.” In Manjhi’s case, Bhagirath did receive four bighas of land from the government, but it was barren. “Not a single grain grows,” he says.

Like Dashrath, Laungi Bhuiyan, another member of the Manjhi community, earned fame for his grit. Over thirty years, he carved a canal through rocky terrain to channel rainwater into ponds and fields across eight to ten villages in Gaya’s Kothilwa village, once a Naxal stronghold.

His story went viral and was celebrated in national and international media. Yet when we visited his home, it found a story much like Dashrath’s—fame without fortune. His mud house still crumbled. Ministers, including Jitan Ram Manjhi, his son Santosh and daughter-in-law Deepa, had all visited, each promising a new home but none delivering.

Laungi says: “They all come, see, promise us a house and a job for my son, then leave. I only ask that one son be given a job and a home to live in.” He has four sons; the youngest, Lalu, aged 28, stays with him, while the others work as migrant labourers. A private tractor company once gifted him a tractor, which Lalu now drives to support the family—a private gesture filling the gap left by public apathy.

Statistics That Speak of Systemic Failure

The Manjhi and Bhuiyan mirror Bihar’s Dalits, who make up 19 per cent of the population, yet over 84 per cent of their households remain landless, according to the Bihar caste survey. A Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS) Mumbai researcher, Krishna Mohan Lal, attributes the Manjhi community’s backwardness to the absence of a traditional occupation. “Among Dalits, those with stable professions like tanning (Chamars), toddy-tapping (Pasis) or pig-rearing (Dusadhs, Paswans) had some economic base. But the Manjhis, historically known as Musahars—rat-catchers—never had a structured livelihood."

He adds that merely having a few leaders or ministers from the community does not transform their condition. “Policies need both intent and execution, something successive governments have failed to ensure.”

From Congress to Caste Politics

Before the 1970s, Dalit voters largely supported the Congress. Later, they shifted toward regional and caste-based parties, first aligning with Lalu Prasad Yadav in the 1990s and then with Ram Vilas Paswan. When Nitish came to power in 2005, he fragmented Dalits further by carving out the Mahadalit category to politically consolidate the most marginalised castes, including the Manjhis.

By appointing Jitan Ram Manjhi as Chief Minister in 2014, Nitish sought to strengthen his appeal among them. For a while, it worked. But within nine months, Manjhi was removed, prompting him to form his own party, HAM (Hindustani Awam Morcha), in 2015. Today, the Manjhis, 3.5 per cent of Bihar’s population, stand behind a divided leadership: Chirag Paswan on one side and Jitan Ram Manjhi on the other, both now allies within the NDA.

Sociologically, the Manjhi (Musahar/Bhuiyan) community represents one of Bihar’s most marginalised groups—landless, poorly educated and excluded from formal employment. Their inclusion in the Mahadalit category was meant to prioritise their development, yet in practice, benefits have seldom reached them. Manjhi’s rise from daily-wage labourer to Chief Minister was a historic moment, but critics say it remained symbolic rather than structural. Even during his tenure, community upliftment was minimal. His party’s recent ticket distribution, giving most seats to relatives or upper-caste allies, has further deepened that perception.

A visit to Manjhi’s village, Mahakar in Gaya district, tells the story of two worlds. The approach road lies in disrepair, but once inside the village boundary, the landscape changes—there’s a middle and higher secondary school, a residential Ambedkar school, an ITI college, a power station, a police post, a hospital, a helipad, a bank and paved roads. Yet barely a kilometre and a half away, in Sapaneri, a Dalit hamlet still waits for clean water, a proper road and steady work. Local resident Aklu Manjhi says: “We’ve seen Jitan Ram Manjhi win since our childhood. He developed his own village but not ours."

Mahakar itself, ironically, has only one Manjhi family among 70 Yadav, 15 Bhumihar and a few Brahmin households, a telling symbol of selective empowerment.

The Politics of Patronage

Veteran journalist Abdul Qadir argues, “Jitan Ram Manjhi never did Dalit politics. He’s always been a puppet of the upper castes, especially the Bhumihars. Even when he was in Congress, it was the Bhumihars who promoted him. In Gaya, old-timers still call him ‘Jitan Sharma.’”

He adds, “Before him, Bhagwatiya Devi, another leader from the community, rose to prominence as both MLA and MP. But she, too, prioritised family. Today, her third generation contests elections.”

In contrast, castes like Paswan, Ravidas and Dhobi leveraged political connections to access reservation and government jobs, something the Manjhis lacked.

Conclusion: From Symbol to Substance

Jitan Ram Manjhi undeniably carved a space for himself in Bihar’s Dalit politics, but his contribution to the social and economic empowerment of his community remains limited. The Manjhi society, despite its symbolic icons like Dashrath and Laungi, continues to live on the margins, waiting for leadership that can move them from representation to reform, from family politics to public good.

Even today, in the villages of Gaya, Jehanabad and Aurangabad, Manjhi families live in mud houses, women work as daily-wage labourers, children drop out of school and government schemes rarely reach their doors.

Between the mountain Manjhi broke and the mountain his community still faces, Bihar’s political symbolism continues to stand tall, immovable and indifferent.

Md Asghar Khan is senior correspondent from Jharkhand

Comments

Post a Comment